The ASU Legacy—Perseverance, Progress and Promise

As a student at ASU, you become part of a select group invited to make this university home for a lifetime— wherever you go and whatever you become, your touchstone can be ASU. You will have opportunities to transform these special years of university experience into steppingstones to the future. You are invited to dream, to see the future’s open door, and to begin the journey. You can take pride in your ASU, and you can add to its legacy. Define your vision and start your journey today.

The ASU Legacy—Perseverance, Progress and Promise

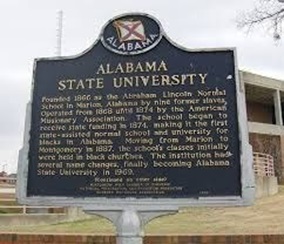

ASU’s 158-year history is a legacy of perseverance, progress and promise. The ASU movement began with the impetus to establish a school for black Alabamians.

The Civil War resulted not only in the end of slavery but also in the opportunity for blacks to have the right to education. With the Northern victory, black Southerners with the assistance of Northern white missionaries and the leaders of African-American churches set out to establish educational institutions for the freedmen. ASU was born in that movement.

Blacks in the Black Belt of Alabama, the heart of the Confederacy, founded Lincoln Normal School at Marion in 1867. As a descendant of that school, ASU is one of the oldest institutions of higher education founded for black Americans. The men who comprised the Board of Trustees were Joey Pinch, Thomas Speed, Nickolas Dale, James Childs, Thomas Lee, John Freeman, Nathan Levert, David Harris, and Alexander H. Curtis. Under the leadership of this group, the blacks of Marion raised $500 and purchased a suitable building site on which a school building was constructed.

Until the new school was built, the American Missionary Association leased a building and operated and financed the school. In 1869, the AMA, with the support of $2,800 from the Freedmen’s Bureau of the federal government and support from the “colored people of Alabama,” raised $4,200 to construct a new building. In 1870, while the AMA provided the teachers, the Legislature appropriated $486 for the school’s use. The state’s support rose to $1,250 the next year.

In 1871, Peyton Finley petitioned the Legislature to establish a “university for colored people,” but his request was denied. He persisted and in 1873 the Alabama Legislature established a “State Normal School and University for the Education of Colored Teachers and Students.” That act included the provision that Lincoln School’s assets would become part of the new school. The trustees agreed, and in 1874 the first president George N. Card led the effort in re- organizing Lincoln Normal School in Marion as America’s first state- supported liberal arts educational institution for blacks.

Black leaders continued to press for a more prominently supported school for black youths. In 1887 the State of Alabama authorized the establishment of the Alabama Colored People’s University. The land and building allocations were put with pledges of $5,000 from black citizens who wanted the university in Montgomery. Thus, the university offered its first class in Montgomery in 1887.

Although university president William Paterson and others had overcome initial opposition to locating the school in Montgomery, opponents of state support of education for blacks remained hostile to the new university. Such opponents filed suit in state court and won a ruling in 1887 from the Alabama Supreme Court that declared unconstitutional certain sections of the legislation that established the university for African-Americans. Thus, the school operated for two years solely on tuition fees, voluntary service and donations until, by act of the Legislature in 1889, the state resumed its support. The new law changed the name of the school from university to Normal School for Colored Students, thus skirting the Supreme Court’s finding and re-established the $7,500 state appropriation.

Despite having to face tremendous obstacles, the ASU family continued to make significant contributions to the history of the state and nation, especially with the involvement of students and employees in the Civil Rights Movement. The Montgomery Bus Boycott, the first direct action campaign of the modern Civil Rights Movement, awakened a new consciousness within the university and the community responded to the call for participants. Even though officials, in a state committed to segregation, retaliated against the school with a decrease in funding, ASU continued to persevere and flourish so that today it is a model of diversity and equal opportunity for all. At the same time, ASU is a beacon in the legacy of black leadership and the preservation and celebration of African- American culture.